ROME PIAZZA FIUME

The 25th issue of Cronache announces to all friends of Rinascente a key moment in the company's history: the opening of the grand new Rome store in Piazza FiumeCronache Rinascente Upim, anno XV, numero XV, 1961

”When the first Rinascente was open, Rome was already a growing city that was touching on one million inhabitants; a provincial town with an umbertino style, popular during the late-nineteenth century reign of Umberto I, with the old clock station on the pediment and a trilussian soul.

In this Rome of sleepy carriages rolling along the sampietrini paving, the opening of the Piazza Colonna department store was a huge event. In the years that passed the building became a point of reference for life in the capital.

You would hear groups of friends asking each other, ‘Where should we get together next time?’; Businessmen would ask each other ‘Where should we meet?’ through crank telephones to arrange an evening of entertainment. The answer was always the same: ‘At Rinascente’.

A new style was born in Rome, the Rinascente style: this functional and luxurious building for the time coincided with the city’s change in tastes.

With its extraordinary size, with its architecture being a level above many other buildings of that time, but also with its ‘homely feel’, this building in Piazza Colonna was the embodiment of a Rome stepping into the very near future - a little less rural, more open to progress, always in harmony with itself, but keeping a fixed eye on Europe.

In the following years, how many buildings in Rome were inspired by the building in Piazza Colonna? How many villas took inspiration from Rinascente’s wide staircase with brass hand railing for their own halls? Many, so much so that the architectural style of that period, preceding the rise of Marcello Piacentini’s era, considered the building as an exemplary model, a style to follow. It is in this way that the people of Rome, the clothes, homeware, furniture and beauty products in Rinascente shaped a style.

Back then, being a Rinascente customer meant rejecting the ‘neighbourhood’ mentality, appreciating progress, and choosing a dining car meal over a picnic lunch when travelling by train.

But time was passing by: even in its iconoclastic dynamism, the demolition and reconstruction of certain rougher districts opened up wide streets, created new expansive neighbourhoods, and rid the centre of undignified hovels and slums to make way for a modern capital.

Once the death knell had sounded for the umbertino style, the style made famous by urban theorist Marcello Piacentini was welcomed in, while the poet Trilussa had no choice but to retire to the loggia of his house to look at ‘those very beautiful August evenings, when the sky was too full of stars if he pitied the luxury of throwing them away’, also writing that: ‘For each one that passes, I often think of the hopes that follow.’

Meanwhile, the city of Rome was increasingly changing its appearance, its habits, and its customs. Rinascente was created for the bourgeois of the centre and immediately broke down the barriers of the innate Roman distrust. It had established itself by widening its area of influence and its clientele from the central neighbourhoods to those of the Flaminio, Prati di Termini and expanding it to an increasingly wider range of social circles. On the threshold of fame, Vittorio De Sica shot his film Grandi Magazzini right in the halls of that building, which would later propel him to fame and glory. Exuding pure opulence, this umbertino-style building, with its wide staircase, the polite and helpful shop assistants, and the first ‘escalators’ in Rome, symbolised a world outside the life of the capital, while staying true to its ‘homely feel’ - which could perhaps have been the main reason for its success.

Because even if the city’s neighbourhoods, houses, streets, and customs had changed, its Roman soul remained intact.

The years inexorably passed, with the river water flowing under the bridges of a Rome that had become international and cosmopolitan, and that formed a style of its own for the world, a new cinematographic language was introduced, while the cars, taking the place of carriages, transformed the delightful Via Condotti of Caffè Greco fame into one of the one-way streets of the quadrangular street system. Riding this wave, Rinascente in Piazza Colonna expanded its sales departments, increased the number of staff, revamped its interior while attempting to incorporate functionality of which even its creator did not have the slightest suspicion, but that was indispensable to meet the demands of a clientele now including all social classes of the city. But changing times meant a changing department store was required. From this, the new Rinascente was given life, in the ultra-modern Palazzo di Piazza Fiume, always at the forefront of progress, continuing its play its role: that of embodying the world of today but also heralding the world of tomorrow.

[...] Opened in the era of electronic calculators and automation, market surveys and increasing motorisation, the Palazzo Rinascente-Fiume is the by-product of all these phenomena, a by-product yes, but Mediterranean, as alive as the flame of the fireplace and unmathematical like the heat of infrared rays. Its location reflects the decentralisation of the high socio-economic status population reported by statistics the availability of parking, and the consolidation of an urban sector home to an estimated 116,000 families (equal to 24% of the total inhabitants in the capital). The inside of the departments designed by the architect Pagani, with its 5000 square metres of sales floor and five escalators to ease the flow of 25,000 customers per hour, was designed to meet the needs of this new Rome of the Sixties, but there was certainly no desire to shut down the Piazza Colonna Rinascente, the exquisite first branch store. Both are evidence of a tradition that is not an end in and of itself, but something that is revamped with the passing of the Tiber’s waters”.

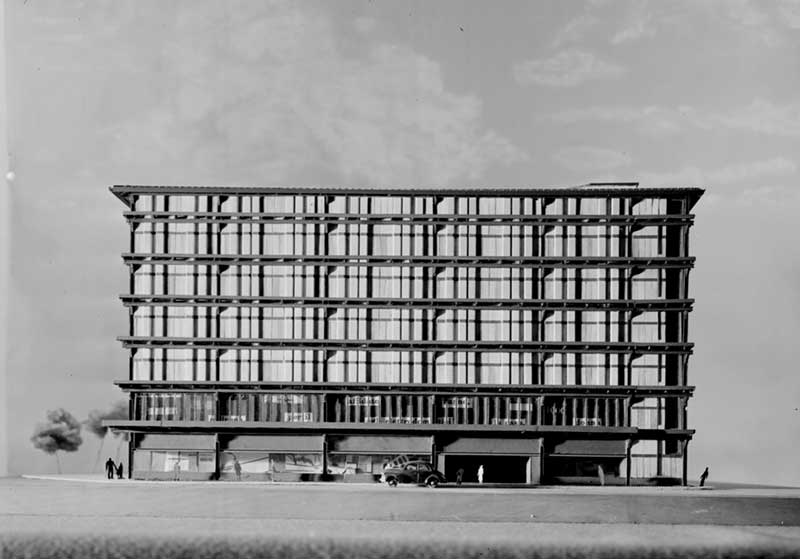

Eloquence of anew form of architecture

1 — Pianta del progetto realizzato della sede Rinascente Roma piazza Fiume; fronte su piazza Fiume, in “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. Il progetto di architettura. Disegni e progetto de la Rinascente di Roma”, 1982

Archivio Italo Lupi

We asked the designers of the Piazza Fiume Rinascene Franco Albini and Franca Helg to discuss the meaning of their work

”The building for the second Rinascente in Rome in Piazza Fiume was conceived keeping the particular constraints of this new architecture in mind: clear urban development restrictions, which imposed very specific spaces and precise volumes, that could be handled by symmetrically adopting the line of existing buildings on the upper façade; restrictions on intended use, due to the department store requiring large undivided rooms and decentralised stairs and service spaces; structural restrictions that required having large lights to allow for the maximum use of space and floors of minimum thickness; and system installation restrictions relating to the large number of specific equipment required by a large department store, which is also needed for certain architectural solutions.

For example, the air-conditioning unit was one of the fundamental problems for us. We ended up solving it in a novel way by using two different units, one on the top floor, the other on floor -3 (instead of one in the basement) to prevent the larger capacity ducts from cluttering the ground floor space where the needs are greater. Once implemented, this solution gave us a starting point for the formal structuring of the façades where the ducts that run along the external walls are incorporated in the pilasters decreasing in size in number from top to bottom.

Having solved the main technical issues before starting, it then became possible to establish a general conception of the building which has a simple and almost classic space: well defined cornices, crafted in the thorough traditional style, complete the composition of architectural elements already in place with the pilasters and iron structural load-bearing elements. These cornices are also where lighting conduits and water ducts etc. pass through, though they do have a very specific aesthetic purpose. In choosing the materials we had to keep in mind not only the recommendations of the Superintendence of Monuments, which required that the building take on a "Roman" character, being colour co-ordinated with the Aurelian walls. There were also specific economic needs that required in the meshes of the structure construction, closing panels made of artificial material (unalterable granulate), which allowed for great savings in space, weight and installation, as well as monolithic channel elements for the pilasters containing the air conditioning ducts. With the subsequent reworking of the first projects, the building therefore took on a rather original plan similar to that of an aircraft carrier, where the use of space is examined according to particular functional requirements so as to decentralise every service and system space towards the outside.

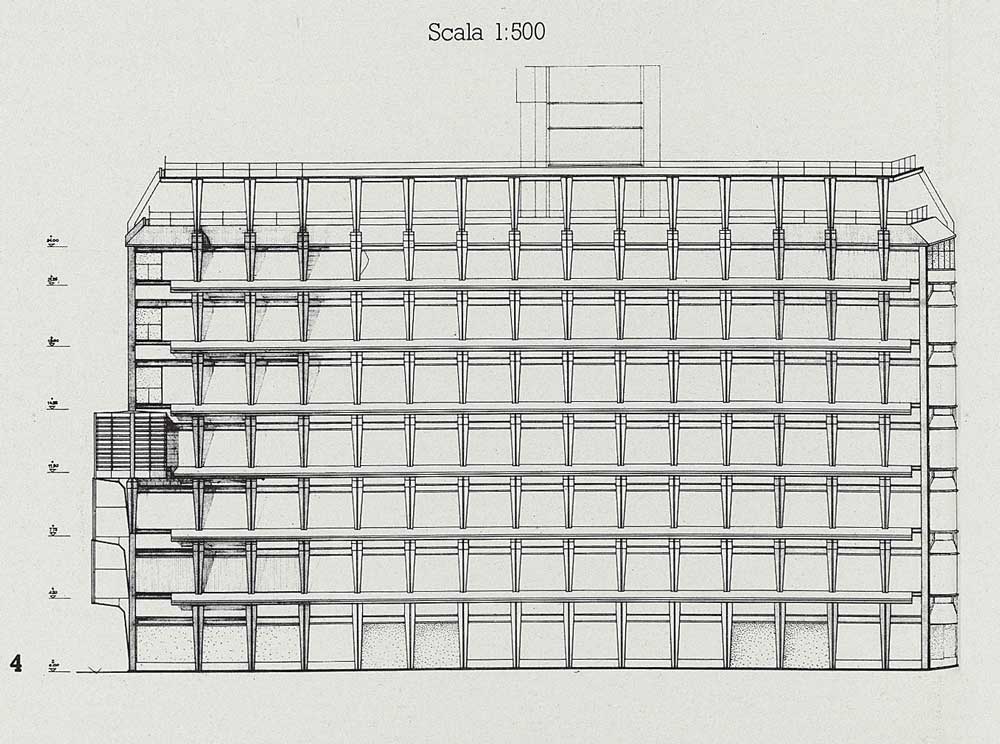

2 — Pianta del progetto realizzato della sede Rinascente Roma piazza Fiume; fronte su via Salaria, in “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. Il progetto di architettura. Disegni e progetto de la Rinascente di Roma”, 1982

Archivio Italo Lupi

The top floor also required a different approach as it was decided that the offices were to be built to allow for natural light to enter. At the same time, we wanted to open a new type of attic window to allow the continuity of the load-bearing structure. It was also possible to respect the form of the cornice with this structure, and install a rail where a wheel-track can be used for window and façade maintenance.

From these complex needs arose bright ideas for the new Rinascente in Piazza Fiume, which gradually took on a specific individuality in the design phase.

It is a building that, due to the importance of its framework, recalls the classic approach of superimposed orders, while aiming to be easily perceived by the lay person. This department store has shown us that, once more, architecture is no longer made only according to the needs of the client but instead it is a social factor which concerns and involves the community, which is to say it not a matter of the exclusivism of the owner, but a general participation in a new building event. The unique character of Rome dramatized this need, and required a project for a building that does stick out in the urban space, but rather wishes to possess a universal eloquence for everyone.

It was in this spirit that the Rinascente in Piazza Fiume was constructed as a piece of non-schematic architecture, one enriched with qualities and happenings that further enliven the interpretation of it - a traditional building that, without indulging in fashions or styles of the time, seeks to interpret and bring life back to the values of tradition in its concise and interpretative conception. In building this new department store, we sought, with the required simplicity, an edifying architectural language that allowed for a significant reconnection with the past and that, at the same time, was ready to accept more developed architectural forms. Using acquired style elements (such as the traditional architraved structure), it was considered necessary to avoid over-the-top structural innovations in Rome and to exclude leading architectural elements. Therefore, we wanted to perform a task that the particular intended use of the work made both tricky and exciting”.

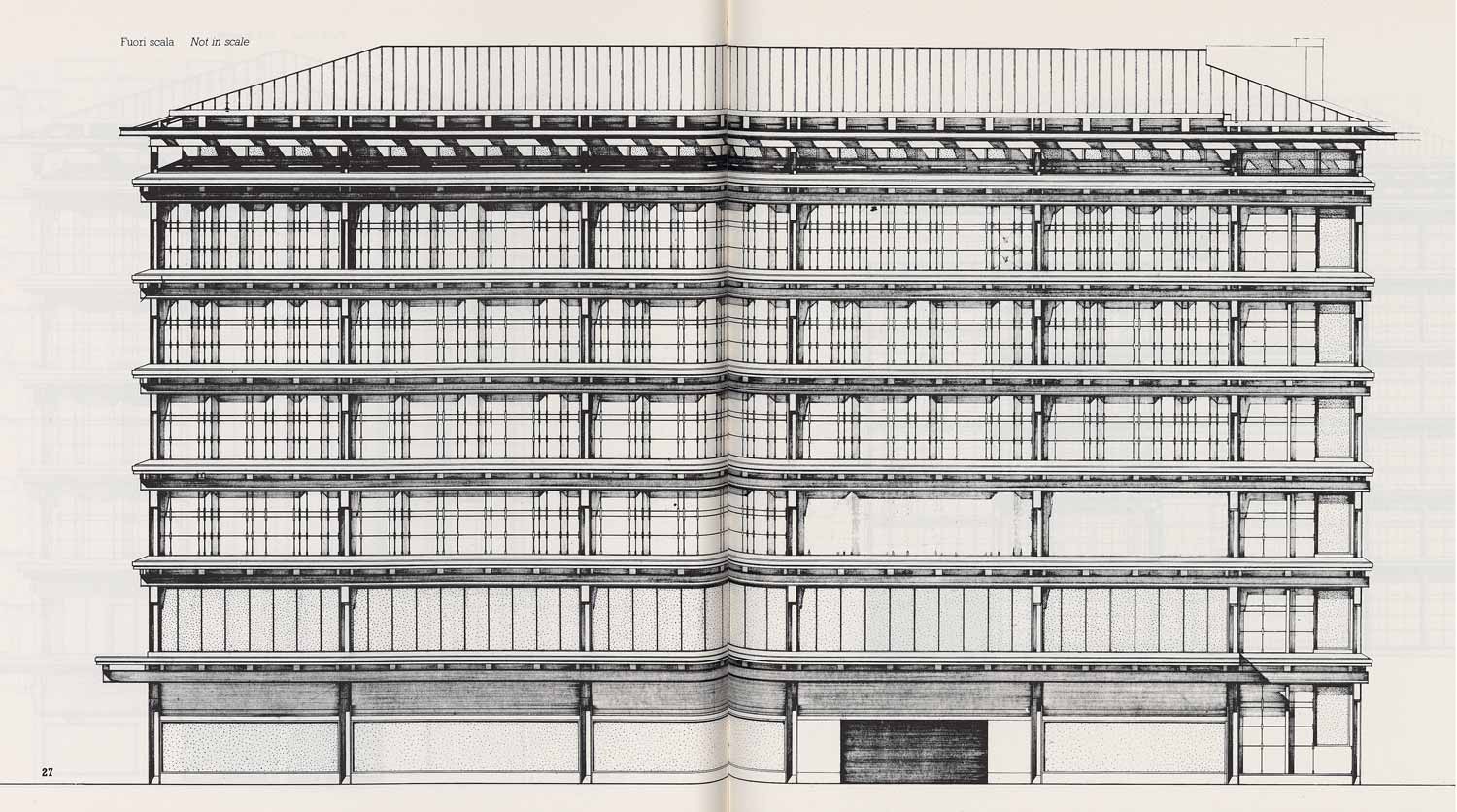

3 — Facciata della Rinascente Roma piazza fiume, in “La Rinascente: cinquant'anni di vita italiana. Volume terzo”, 1968

Archivio Amneris Latis

Rome Piazza Fiume

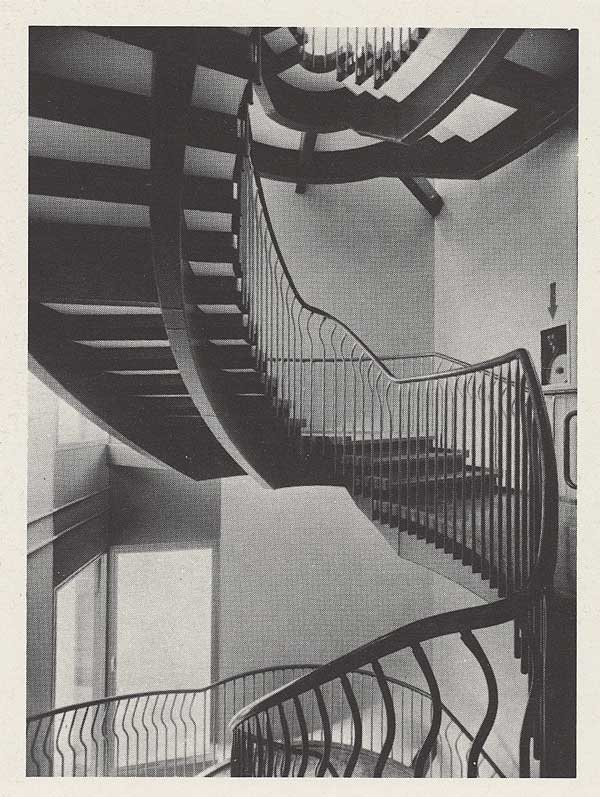

4 — La Rinascente di Roma piazza Fiume. Scala elicoidale, [1962]

Fotografia: Giorgio Casali

Archivio Progetti, Università Iuav di Venezia - Fondo Giorgio Casali

A second department store for a great international centre. A fabulous and elegant international boutique across seven floors.

5 — La Rinascente di Roma piazza Fiume. Veduta del reparto mobili, [1962]

Fotografia: Giorgio Casali

Archivio Progetti, Università Iuav di Venezia - Fondo Giorgio Casali

6 — La Rinascente di Roma piazza Fiume. Veduta del reparto uomo, [1962]

Fotografia: Giorgio Casali

Archivio Progetti, Università Iuav di Venezia - Fondo Giorgio Casali

”From mid-September, Rinascente will open its doors to the women of Rome as the largest boutique they could possibly desire.

The ladies of the Parioli neighbourhood will come to this store, sometimes accompanied by their husbands, but busy bachelors will also be there for the upkeep of their city apartments.

Everyone will find the ‘something’ to suit them over the seven floors, with air conditioning reminiscent of the ponente breeze that gently moves the embassy flags under the sun of the Roman hills.

The Piazza Fiume Rinascente is the first department store with air conditioning that, to a certain degree, also functions as the entrance, a symbolic door removing any barrier between the people outside and what is inside. The undecided buyer therefore need not worry about finding the right time to pull down a handle or to push a door open. There is no specific ‘moment’ needed to cross an air curtain, characterised by a few more or a few less degrees, just enough to entice the passer-by to become a buyer.

They will be able to wander the seven floors and discover numerous product sections. In the basement you will find homeware, electrical appliances, sounds enclosed in disks with their related instruments, and three listening booths. On the ground floor, the scents of essences and leather goods will come together, the haberdashery will sit alongside woollen yarns, hosiery alongside footwear, and stationery alongside the ‘photo and cinema’ section. The entire men’s department is on the first floor, to dress men from head to toe, and includes sportswear.

The children’s department and textiles are found on the second floor, placed together perhaps because textiles are among the more durable goods when it comes to children, the main customers of that floor. To take women away from the tea room and bar would have practically been a punishment for them, so the third floor houses ‘everything for women’, and that truly seems to be the case. On the fourth floor upholstery, luggage, sports equipment and toys are to be found. On the fifth floor houses furniture, furnishings, lighting and an area for special exhibitions, the first of which will be held at the opening and will explore the theme of schooling [...]. 250 employees work on these seven floors with a countless number of product categories. The junior-level employees cut their teeth and learned the ABCs of modest salesmanship in Rome, while the higher level employees, like department heads, acquired their experience in Milan. In a nod to the ‘grande boutique’, there is a Swiss man who combines the precision of the cantons with exuberance, cordiality and Latin liveliness. He is Stefano Broquet, who has been at Rinascente for years. The 5000 square meters of sales floor include details of every kind imaginable. The customer would feel lost in front of such a large quantity of goods if the staff were not always at their service, even for the most obvious questions.

7 — La Rinascente di Roma piazza Fiume. Veduta del reparto libreria, [1962]

Fotografia: Giorgio Casali

Archivio Progetti, Università Iuav di Venezia - Fondo Giorgio Casali

8 — Reparto attrezzi sportivi, Rinascente Roma piazza fiume, in “La Rinascente: cinquant'anni di vita italiana. Volume terzo”, 1968

Archivio Amneris Latis

The architects Carlo Pagani and Gian Carlo Ortelli oversaw the furnishing of Parioli neighbourhood’s ‘grande boutique’. Both designers of the Genoese Rinascente, they were excited about the occasionally interrupted sales floors, which had been made necessary at that location due to construction needs and where the sales departments were laid out. The ups and downs and interrupted floors created a world full of surprises for the customer to enjoy that was also profitable. The continuity in Rome was broken all too easily as well, but above all an attempt was made to avoid any rift between customer and goods.

All the furniture for displaying goods is completely new, particularly more durable plastic laminates. In order to achieve this, the paint was stripped throughout the store and whatever else was deemed to hold the design and feel back in time went as well. Rubber flooring and carpet were installed in alternation depending on the floor. Rubber is used in the homeware department to convey a greater sense of cleanliness, while the carpet is found in the tailoring and clothing areas, making every step a soft one, as soft as the approach to take when revealing what purchases you made in this department to your husband.

Lights of hundreds of lux per metre, fluorescent in the more delicate areas and incandescent for the women’s and furniture departments, create the most enticing lighting possible, recalling leisure and family warmth, cleanliness and intimacy.

But the novelty of this arrangement of merchandise, with vigilant shop assistants often serving as personal shoppers, is the type product grouping that puts various products together according to their intended use [...]; for example, the kitchen cabinets have been placed in the homeware department. This makes a potential purchase easier, and so among the pale tones of the women’s departments, the green hues with wood elements for men’s department , and next to the fragile product sections for the home, the customer finds the finest items they could desire, combined with the best products available”.

Franco Albini and Franca Helg's Rinascente “Albini-Helg Rinascente. The architectural project. Designs and the project of the Rome Rinascente”, 1982

9 — Pianta del primo progetto a campata unica de la Rinascente Roma piazza Fiume; fronte sulla via Salaria (montauto sul fianco ovest, scala esterna su piazza Fiume), in “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. Il progetto di architettura. Disegni e progetto de la Rinascente di Roma”, 1982

Archivio Italo Lupi

In 1957, Rinascente commissioned the Albini-Helg studio to design of the new Rome store. The Lombard architects’ work in Rome is a rather exceptional feat. The two designers are exponents of that Milanese culture which, at the beginning of the modern movement in Italy, had defined itself with very different characters from the Roman environment. The rift had subsequently widened post-war with the establishment of two fronts: the first favoured a rationalist approach, the other, a more organic style.

The difference in cultural choice was accompanied by a traditional rift between the social realities of the two areas of the country and by a different commission - represented in the former by the active industrial bourgeoisie, in the later by the Italian State and the bureaucratic-ministerial practice. This became over time almost a division of the spheres of influence and highlighted the atypical nature of Milanese architects working in Rome. This exception that is the Rome Rinascente is confirmation of what has been said, as the building was commissioned by a northern business group. Excluding the era of the great twenty-year competitions and the attempts at opportunistic and temporary alliances, such as that of Piacentini for the university city, there are rare cases of Milanese firms that have had the possibility of working in Rome, and while cases like that of the B.B.P.R. in the 1940s and the post office at the EUR could be mentioned, we must consider that these were almost always interventions performed outside the “real city”.

The difficulties were therefore twofold: a certain mistrust of the local professional environment, which sees its own field being invaded, and the objective difficulty of becoming a part of an urban reality very different from the already difficult daily one when historical memories and prestige are involved. Designers are well aware of these difficulties and proof of this is the commitment with which they tackle the theme, providing the Roman environment with an example of technological clarity that would be a cornerstone in the activity of the younger generations of local architects. The place chosen by the clients for the building was Piazzale Fiume on the corner of the Via Salaria, a space characterised by the imposing stature of the Aurelian walls and by the late nineteenth-century residential buildings, though it would not be a topos with remarkable characteristics if it were not for those mighty and ancient brick walls.

Although at the time of the assignment the square did not suffer the congestion it has today, an increase in the volume of traffic conveyed by the Salaria and the resulting residential expansion already in progress was foreseeable. This created a sense of doubt about the urbanistic possibility of the choice, and allowed for a glimpse into the inevitable danger which would be encountered - that of facilitating such congestion with the creation of a structure that by its nature attracts large swathes of people during peak hours.

To avoid these inconveniences as much as possible, Albini and Helg decided on a compact and closed space that conforms to the street network without splintering off from the models of the surrounding buildings. In the first extremely successful structure, a large garage on the roof underscored its autonomy and the desire not to contribute further to the already congested road system of the city. Eventually rejected by clients for various reasons, this first project design remains among the most pleasant structures ever designed in Italy, though not just Italy, at the end of the 1950s. It deserves, however insensitive a description of an unrealized building might be, an accurate analysis in view of a comparison with the final project. The building type requested is that of every large modern department store - a voluminous space with overlapping floors, equal and flexible surfaces so as to blend in with one another, and uniform artificial lighting, which requires being closed off from the outside. But this first structure bears a perceptible distribution innovation (which is, at the same time, an element of attraction in line with the consumerist logic of this type of building) namely, the large car park on the top two floors; perhaps a call back to that track that Giacomo Mattè Trucco had designed for the Fiat Lingotto in Turin and that in the 1920s had fascinated Le Corbusier himself.

10 — Pianta del primo progetto a campata unica de la Rinascente Roma piazza Fiume; fronti su Corso Italia e via Aniene, in “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. Il progetto di architettura. Disegni e progetto de la Rinascente di Roma”, 1982

Archivio Italo Lupi

The building has a total of ten floors: three of them underground, seven above. The basement floors are in reinforced concrete, as are the two service blocks and the vertical access between floors, one of which overlooks the top floor of the car park. The above-ground floors are all dedicated to sales, offices and stock rooms, and have an exposed iron structure consisting of variable-section double-T portals hinged to the supports to allow for the removal of the internal pillars. Along the main façades, the piers of the portals remain in full view, the thickness of which is consistent with contemporary trends. The shape of the iron beams curves to follow the form of the top floor, acting as a tie bar to hold up the top level of the car park. The reference to the 19th-century tradition of the great iron architecture of Parisian department stores and London greenhouses and exhibition halls is clearly evidenced here. An unequivocal confirmation of a repertoire of forms is given by the function of the chosen structure. The beams connecting the portals run at a lower height than the internal slabs. On the façade there is a conduit for the air-conditioning which takes on the role of an evident stringcourse, anticipating the theme that will be the basis of the façade composition of the second project, namely that of exploration of the technical problems that results in the formal structure.

The front facing Via Salaria, densely marked by the chiaroscuro interplay created by the elements of the portals and cornices, looks out onto the square where, since the single span is no longer needed, the simple pillar structure with limited-span beams is apparent. But there is no juxtaposition of the two, as the main façade extends ‘naturally’ over the smaller one thanks to the key element of the external body of the staircase that surrounds its corners and runs along it diagonally, recalling aspects of German expressionism and in particular of Gropius; one need only mention the glass body of the office staircase at the Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne or the project for the Chicago Tribune building. The curtain walls are covered with vertical travertine slabs, while the bodies are made of reinforced concrete and masonry. The air conditioning, the fire prevention system and the lighting are all integrated in the load-bearing structure. But while this first project was both a perfect formal and technological structure, it was not accepted by the client and the studio designed the building from scratch.

Having scrapped the first structural plan with the iron portals that marked the façade, the designers focused on the planed panels that replace the dense chiaroscuro interplay of the vertical elements of the first project; a less marked vertical structuring that varies according to the path of the integrated HVAC piping housed there.

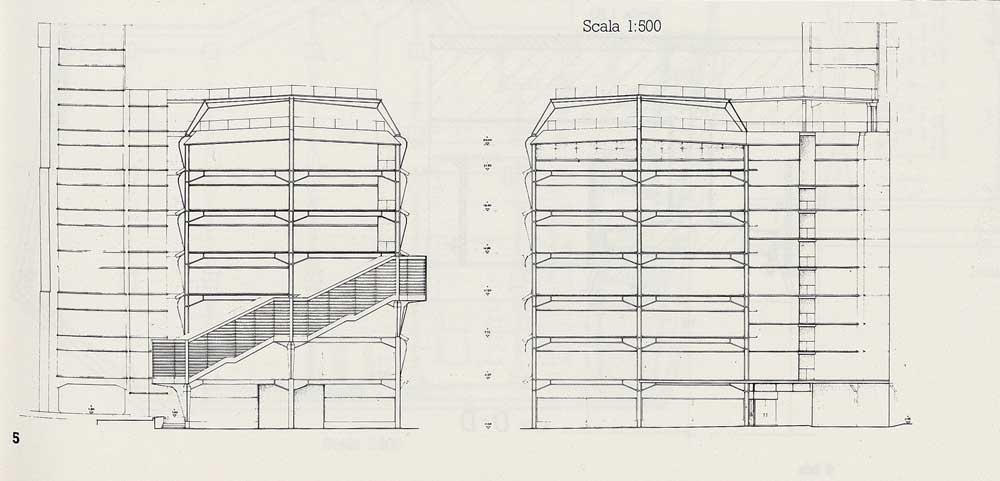

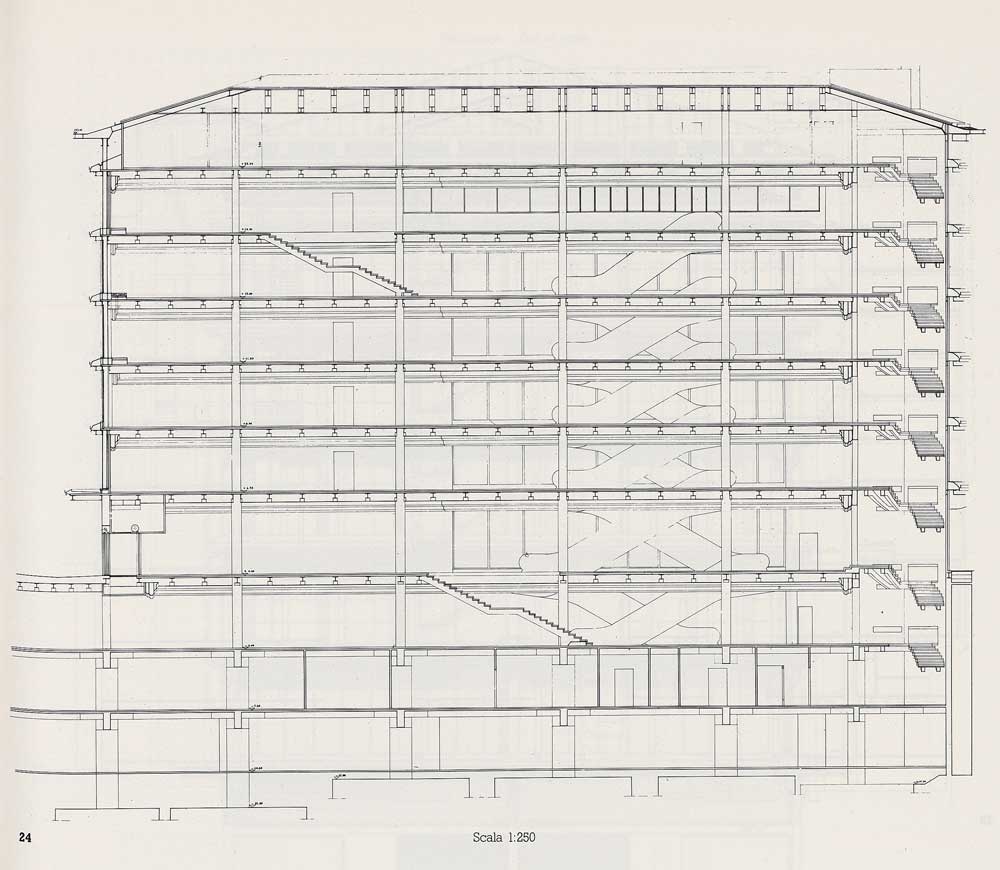

11 — Sezione trasversale del progetto realizzato della sede Rinascente Roma piazza Fiume, in “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. Il progetto di architettura. Disegni e progetto de la Rinascente di Roma”, 1982

Archivio Italo Lupi

Indeed, the functional needs of the systems, now brought to the surface, suggest the formal plan is structured in the shaping of the light prefabricated panels of grain granite and red marble, and in the sheet-metal stringcourse that houses the horizontal ducts. Here too there is a diversification in the structure, made of reinforced concrete up to the second basement floor, and made of iron from the first basement floor to the roof. The steel framework determines the division of the outer surfaces with vertical struts, and consists of a main frame that runs longitudinally and a secondary truss of iron beams, remaining evident on the outside. The volume is then completed with the coping of the large iron frame, protruding from the edge of the façade so as to allow a trolley to run along its perimeter for future maintenance of the façade.

Rinascente soon became one of the models of Italian architecture and one of the most celebrated buildings, the subject of pages and pages of text. Above all, there was an insistence on maintaining the relationship between Roman architecture and the city itself, analysing it from different historical and critical angles and offering different interpretations. The designers were also attentive to the environmental needs of the building while working in such a rich and characteristic urban scene. This has channelled the critics’ interest into the relationship with the architecture of the Roman building that many believed to find evoked in contemporary constructions through the historical nods found in many of its elements. In the clear horizontal band that runs along the planed panels, an allusion to an intersection of the orders of Mannerist influence is seen, as well as a classic reference in the arrangement of the heads of the beams projecting under the horizontal duct elements, in the spirit of the bourgeois architecture of the beginning of the century.

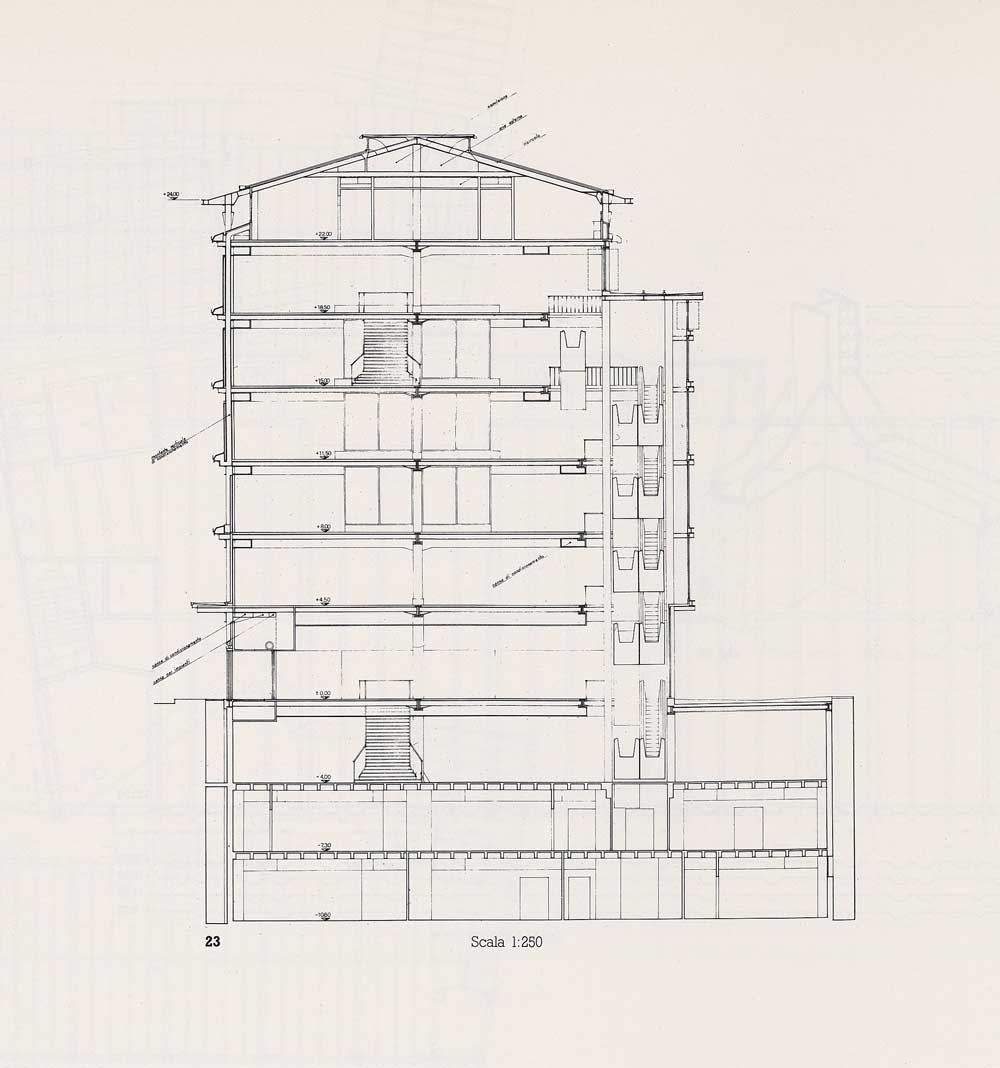

12 — Sezione longitudinale del progetto realizzato della sede Rinascente Roma piazza Fiume, in “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. Il progetto di architettura. Disegni e progetto de la Rinascente di Roma” 1982

Archivio Italo Lupi

Beyond these somewhat contrived arguments, the rigid and even Renaissance-inspired structure of the building undeniably bears some semblance to Palazzo Farnese. Albini and Helg do not resort to acclimatisation, but instead reinvent the memory of the traditional Roman building. This idea is clear when considering the roof, with its iron frame protruding out from the edge of the façade, which ironically seems to be a nod to Michelangelo's cornice in Palazzo Farnese. [...]

In the work, many have seen an overcoming of, or in any case a detachment from those principles espoused by the modern movement that had been the basis of the studio’s dedicated research for many years. First, the substitution of the pure, rationalist and traditional relationship between a more evident structural mesh and transparent cladding elements which do not break the external-internal continuity, and a different relationship in which the main role is to infill with its consistency and its colour, placing the structure in the background, taking on a secondary role.

13 — Scala elicoidale vista dal basso, Rinascente Roma Piazza Fiume, in “La Rinascente: cinquant'anni di vita italiana. Volume terzo”, 1968

Archivio Amneris Latis

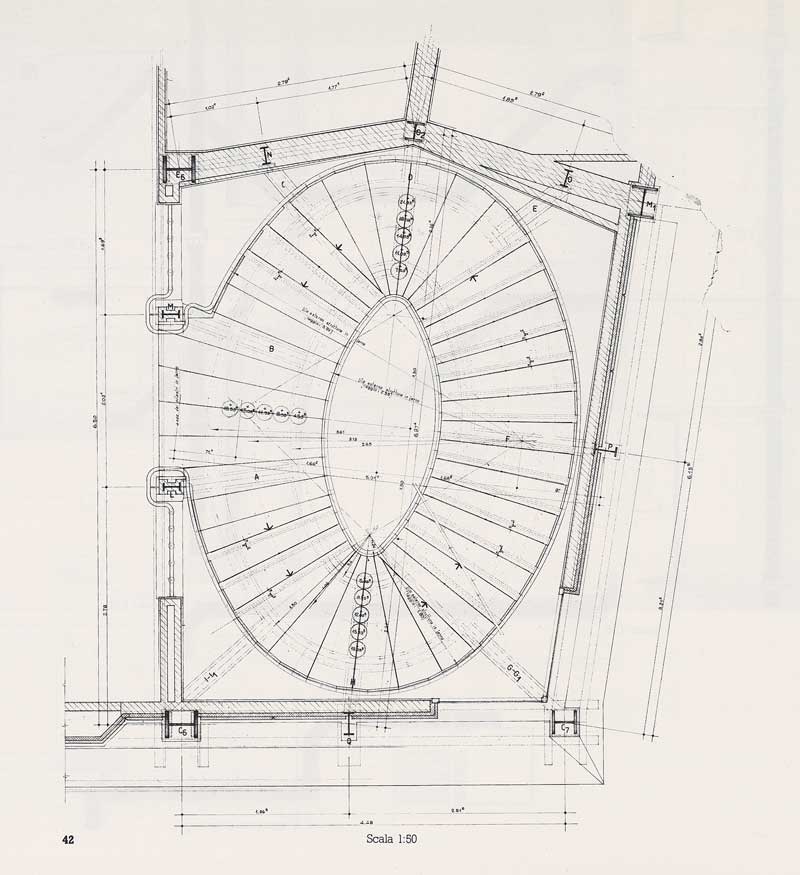

14 — Scala elicoidale riservata al pubblico, posta nell’angolo fra via Salaria e via Aniene, Rinascente Roma piazza Fiume, in “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. Il progetto di architettura. Disegni e progetto de la Rinascente di Roma”, 1982

Archivio Italo Lupi

15 — Particolare della scala elicoidale, rinascente Roma piazza Fiume, in “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. Il progetto di architettura. Disegni e progetto de la Rinascente di Roma”, 1982

Archivio Italo Lupi

The absence of a particularly evident typological in-depth analysis, although not entirely attributable to the designers, has given rise to many doubts. The lack of a correspondence between internal and external space has also been interpreted as the overcoming of a more functionalist methodology in favour of a procedure which connects the exterior of the building to the urban context and the interior to the functions that are required of it.

But the designers reject the accusation of having eschewed the principles of the modern movement in the name of an up-to-date and technologically persuasive continuity of the new way of building that acts as an answer to the question of their times. For them, the teaching of the modern movement is ‘a moral lesson in cultural honesty and expressive sincerity that is a barrier to poetic license, but it is not a limit to ideas which are refined or rich in expression’.

It seems to be that the most intelligent interpretation, which goes beyond the analysis of the building's so-called formal and stylistic values, is given by Reyner Banham when he highlighted the qualities of a machine designed specifically for a proper control of the environment. It also underlines the fact that both in the first and in the second project structures, the study poses the problem of environmental control as a privileged design guide. He attributes a theoretical importance which he derives from the double role that the casing plays with the environment in the project - the passive role of a barrier to prevent external climatic conditions encroaching into the interior; and vice versa, the active one of ‘distributor of air conditioning and environmental energy’.

Confirmation of the high esteem that the building has been shown by international architectural critics can be seen in Banham's own views and in the fact that the Anglo-Saxon criticism considers this architecture to be a model to be used alongside Louis Khan’s Richard labs in Philadelphia, and Marco Zanuso’s factory in Argentina.

Interview with Franca Helg “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. The architectural project. Designs and the project of the Rome Rinascente”, 1982

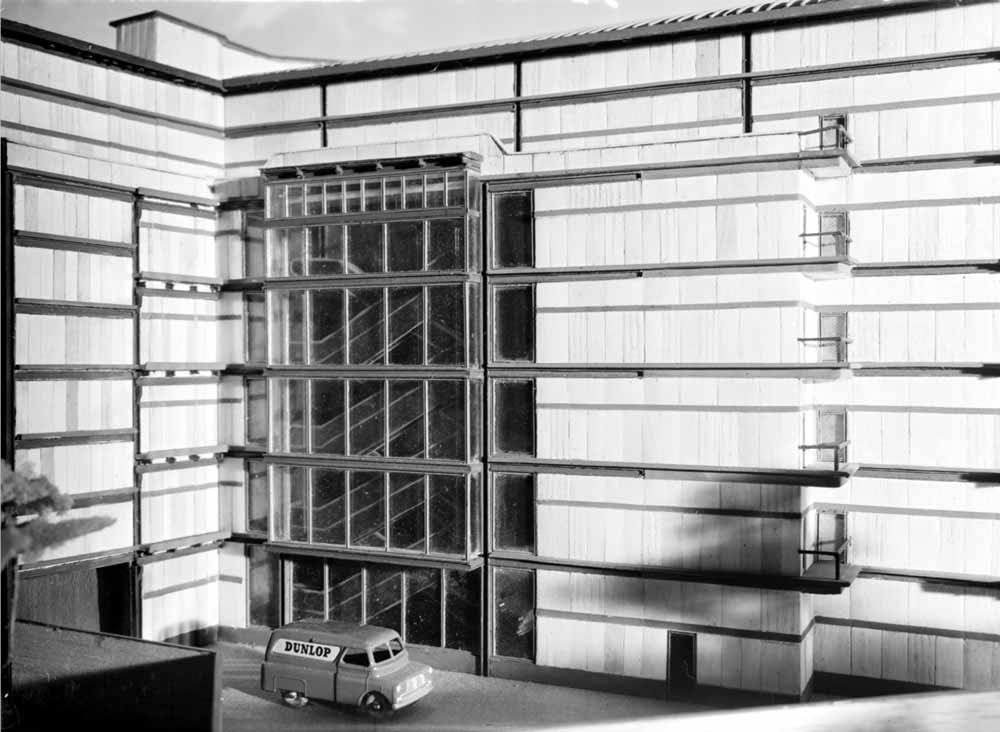

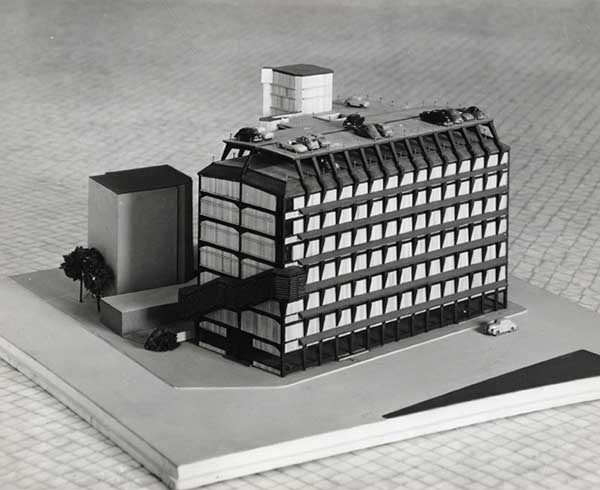

16 — Modello del progetto di Franco Albini e Franca Helg per i magazzini la Rinascente di Roma piazza Fiume, [1957 - 1960]

Particolare del modello con la vetrata sporgente in corrispondenza delle scale mobili

Fotografia: Giorgio Casali

Archivio Progetti, Università Iuav di Venezia - Fondo Giorgio Casali

17 / 18 — Modello del progetto di Franco Albini e Franca Helg per i magazzini la Rinascente di Roma piazza Fiume, [1957 - 1960]

Fotografia: Giorgio Casali

Archivio Progetti, Università Iuav di Venezia - Fondo Giorgio Casali

‘In my experience it is not often that there is a comparison between the analysis, critical hypothesis and motivations, conducted by those who design, for their own designs. The critic's reading of a work speaks to what the critic sees, knows and senses in their own mindset, a Weltanschauung linked to their own culture and ideology.

Those who work often have more intimate reasons linked to their own ideology, which can more or less correspond to that of the critic, but also and above all linked to their existential problem of expression without considering that the contingent reasons, quality, character, needs, availability of the client, the costs, the conditions of the places, the legislative aspects, the bureaucracy and all the considerations that may also seem trivial encroach into the concept for the project and in some way impinge upon the idea itself. What is more, in the actual doing of the work, conditions sometimes change. When the work is finished, these conditions, which are also intrinsic to the work, leave no trace of memory, and least of all the critics cannot be remembered. However, criticism is fundamental and useful both culturally and didactically with regard to its interpretation, for the analysis of the expressive language, as a deconstruction of the work into its constituent parts, to clarify the link between these elements and the formal effects that arise from it, and for the analysis of the interactions between society, customs, economic conditions, technological possibilities, and constructive opportunities.

In criticism, it is vitally important to create new ways of interpreting that broaden the debate and allow even a distracted public to participate culturally speaking in the enjoyment of the work, ways of interpreting that develop the awareness of future generations of professionals. But often this useful interpreting cannot be shared by the author because the author's reasons are outside of this. The designing itself, in my opinion, is of a different nature than the critical one. Even if conducted with rational rigour, if punished by a continuous and severe verification of the coherence between proposed solutions and the intrinsic and extrinsic details of the problem, it has in itself a share of sensations, feelings, and intuitions too deep and personal to be enumerated with the clear coldness of criticism. After all, there is a sense of shamelessness for those who have designed and created something, in explaining the reason for the choices, and it is already taken for granted that it will be impossible to explain any of their reasons: silence in this regard is not just a contemporary issue.

However, I will try to convey more than the reasons for analytical choices, the spirit that inspired this design. Over twenty years have passed, but I still remember our passion for and attachment to this job. For architects who learned their craft in Lombardy, who for many reasons out of their control have built few buildings, the opportunity to make a relatively large building in Rome, in front of ruins of ancient walls, in surroundings of such a broad and contradictory complexity – in which sumptuousness and spontaneous articulation closely intertwine – is an opportunity to accomplish a great feat, yet coming with a great deal of perplexity. In 1957, when our relationship with designers and the competent authorities of the Roman municipality began, the crossroads of Piazza Fiume was not affected by the traffic of today. However, it was evident that the Via Salaria, gathering together a large area of residential expansion, would have funnelled a much heavier traffic load into the city. In the administrative and planning structures of that time, and perhaps even today, there was no opposing the logic of the department store, that by its nature led to rush hour moments with large crowds, in one of the city’s nerve centres, where any incentive is undoubtedly harmful.

19 / 20 — XII Triennale di Milano. Modello in scala del secondo progetto dell’Edificio per un grande magazzino de la Rinascente a Roma, 1960

Materiale esposto nella sezione dedicata a Franco Albini delle mostre personali di architettura

Fondazione La Triennale di Milano - Biblioteca del Progetto e Archivio Storico

Although these obvious considerations regarding urban possibilities could not be accepted by the client, they did however help us decide on a compact and closed space that was part of a road network, without creating dramatic alterations to the urban pattern. Not producing works detached from the context, but rather things that are part of the context, almost as if they had always existed is an implicit aspiration in our way of working. This desire is linked to that of contributing with one's work to enriching the history of the city (or the construction or physical environment) and entering into the stratification of history with an attention that takes place between two binary positions: a respect for tradition on the one hand and the need to express oneself in the appropriate ways of our time on the other. Tradition, it has been said, is the collective consciousness of the continuity between the present and the past, the continuous integration of the values of the customs, ethics, and culture of every era in history, a sort of collective recognition of permanent cultural values. The needs of our time are those of our way of living, of producing, of existing; they are our historical moment - and not those fictions of trends. Even if not always consciously expressed and not always achieved, one of the salient points of our design interest is the search for a balance between these binary p

When working on a project in Rome, in an exceptional environment filled with memories and history, the search for a piece of architecture that respected the city, interpreted some of its salient features, and was at the same time an authentic contemporary expression was the dominant creative energy. This search entailed numerous aspects: volume, structure, divisions, materials, colours, details, everything. [...] We feel deeply connected to the rational method of planning and to the discipline of rigorous verification of the Modern Movement. [...] Now that the axiom "form must adhere to function" is ubiquitous, the formal enrichment of architecture does not contradict the teaching of the Modern Movement. [...]

For us the fundamental desire was to create a container and place it in a cemented urban fabric, an "urban" structure that is not necessarily monumental, but nor is it sloppy or inoffensive, something that achieves dignity and an architectural characterisation (as well as being in compliance with current legislation), constructive opportunities, internal flexibility requirements, etc. All the component elements, the structural ones, the technological ones, the infills, the windows, the roofing, the materials, the colours, are all always linked by mutual interrelations. In the long, patient, iterative work of the design, alternative possibilities of use and individual component design elements were analysed, studying the detail in relation to the overall composition very closely.

21 — La Rinascente Roma Piazza Fiume, in “Albini-Helg La Rinascente. Il progetto di architettura. Disegni e progetto de la Rinascente di Roma”, 1982

Archivio Italo Lupi

22 — La Rinascente di Roma piazza Fiume. Particolare del fronte esterno con la vetrata sporgente in corrispondenza delle scale mobili, [1962]

Fotografia: Giorgio Casali

Archivio Progetti, Università Iuav di Venezia - Fondo Giorgio Casali

The building of Rinascente along the Via Salaria closes the road and reassembles Piazza Fiume. The structural division of the building is a technical choice, but at the same time, is an architectural choice for a proportion that sets the space into a calm rhythm. The profiles of the already beautifully designed steel beams are used as architectural frames. The heads of the secondary trusses, in view, increase the value of and provide references to the perception of dimensions with the fading away of the shadows. By placing these technical elements along the perimeter, the panels that swell to contain the system ducts become a technological solution which allows for great internal usability, but they are also a stylish and boast a chiaroscuro effect. The variation of the infill corrugation with decreasing intensity from top to bottom corresponds to the decrease of HVAC ducts, and is also an element of variation in uniformity, becoming more dense along the road and more stretched out towards the square. The wheel-track for maintenance and cleaning of the façade meets the precise needs of the trolley and its arm, but is at the same time careful to reflect the coping of the houses all around. Baroque memories? Or the bourgeois architecture of the beginning of the century? I do not know. We have often talked about “irony” in certain project structures proposed by our studio, and perhaps it has been said for the “simulacrum cornice” as well. It does not seem to be a question of irony to me. The architectural elements, even considering freedom from tenets, are in our visual memory. A building of that proportion, with those horizontal and vertical divisions, needed to be coped in order to re-enter the context and round off its volume.

Finally, why that colour? Why that material? The monument to the Unknown Soldier in Piazza Venezia is made of botticino, a beautiful marble for the fountains of Brescia, but leaden and inert in the bright space of Rome, while the bricks of the ruins of San Sabina or Saint John Lateran are rich and luminous. The material for the new building in "curtain wall" had to be prefabricated, possess a vivid grain and colour, yet not be gaudy, and had to resistant to the city’s air, much like the turn-of-the-century cements. For us, the analysis and the study of both of the detail and of the whole are guided not only by a “how is it done?”, but also at the same time and closely interrelated, a "how do you see it?". The details, technological and formal structures are recomposed into a synthesis whose many elements must achieve a single, consolidated structure. Things conceived and executed by others, both ancient and contemporary, are a part of our experience, they are within us, and in our proposals elements already experienced that are in everyone's architectural culture resurface. The relationship with internal and external collaborators, system and structure experts, the design implementers, has entered this patient and intense game to arrive at a solution that takes into account each sector’s every need and which was nonetheless controlled from the point of view of balance and formal characterisation.

Franco Albini used to say that just as without friction one cannot walk, one cannot design if there are no constraints. The conditions should not be considered impediments, but rather incentives. Again, a "moral" attitude placed us in a position of an easy collaboration with specialised technicians and that helped the participatory understanding of the design implementers”.

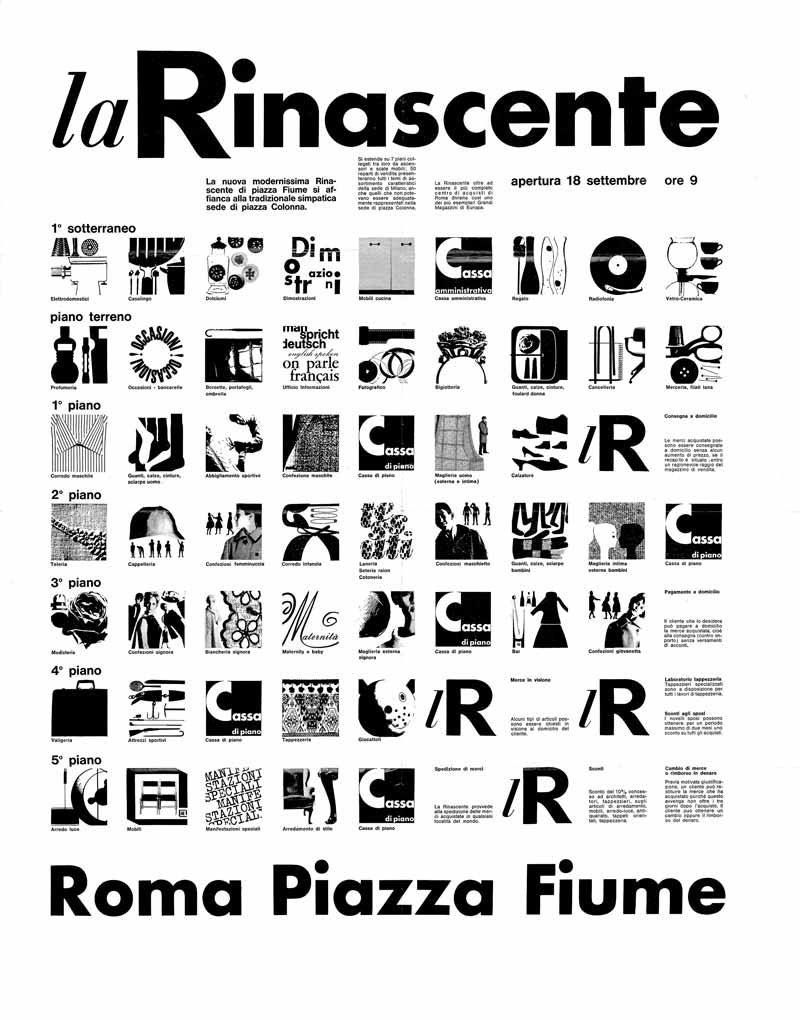

Rome, Piazza Fiume 16 september 1961

All the people of Rome wanted a new Rinascente Cronache Rinascente Upim, anno XV, numero 26

23 — La Rinascente, Roma piazza Fiume. Apertura 18 settembre, 1961

Poster

Progetto grafico: Lora Lamm

Archivio Gian Carlo Ortelli

The main entrance of the new Rinascente in Piazza Fiume in Rome was lit up by powerful spotlights in the twilight hours of 16 September. Positioned among the trees, the lights illuminated the red and blue plume of the Carabinieri military police uniform, gleamed off the gold on the ceremonial uniforms of the Vigili Urbani municipal police, and brought vibrancy to the countless colours of the lively crowd huddled together to watch the arriving guests up close, making jovial remarks on the event unfolding. On the other side of the door, wide-open as a welcoming gesture, the guests stopped for a moment to take in the entire department store that all of Rome was talking about.

Before the arrival of the guests, the President wished to cordially greet the staff in order to praise and thank them for their hard work and wish them well for the future. On behalf of all the employees, two very young apprentices offered two symbolic gold keys to the store to Order of Merit for Labour recipient Umberto Brustio and Aldo Borletti. The honorary president Umberto Brustio, the president Aldo Borletti, the vice president Cesare Brustio and the general manager Giorgio Brustio did the honours by opening the store, with the many friends of Rinascente in attendance at this special event. They immediately felt at home thanks to the smiles of the helpful salespeople who were politely attentive and had a good-natured interest in assisting the guests.

There was a palpable interest evident from the crowd, to the extent that they explored the shopping floors as if embarking on a light-hearted treasure hunt, in search of the latest goods.

After a blessing of the new building was given in Latin by the Archbishop Vicegerent of Rome, Mr Borletti took to the floor to give a warm welcome to everyone and once again gave his heartfelt thanks to everyone attending. “This new store adds to the old and glorious one in Piazza Colonna, which at a painful and distant time represented the only dynamic aspect of our organisation. Forgive me if on a day that should be full of joyous celebration, I bring up a sad memory from the past. I do so because this store that opens its doors to the public of Rome is not only a complex and complete realisation of a project in itself, it forms part of a ring, albeit a particularly shiny one, made from a chain of determined work performed by many people who have shaped and reconstructed this project with a self-assured effort”.

24 — L’onorevole Campilli visita la nuova filiale Rinascente accompagnato dal Vice Presidente Cesare Brustio, in “Cronache laRinascente Upim” 1961, anno XV, numero 26

25 — L’Arcivescovo Mons. Cunial, Vice-Gerente di Roma, dopo aver impartito la benedizione si intrattiene con il Presidente Dott. Borletti, in “Cronache laRinascente Upim” 1961, anno XV, numero 26

After stressing that the new store is part of the 85 Upim complexes and one of the 7 Rinascente stores, Mr Borletti mentioned the architectural issues of the new building that had to be overcome. He thanked all those who collaborated in its construction and underscored the passionate work of all the corporate bodies and staff who completed the preparatory work with much enthusiasm. "We are aware,” he said, “of having acted not only in the private interest of a large company, but also in the advancement of a cause that I believe to be highly social in nature: distribution work, not always considered and appreciated as it should be, is clearly evident throughout this construction in all its importance”. After thanking the authorities present, Mr Borletti concluded:

“On behalf of the twelve thousand collaborators and with a strong faith in the prosperous future of our country, I now declare the new store in Piazza Fiume officially open.”

Minister Campilli, president of the National Committee for the Economy of Labour, wished to conclude: ‘with the hope that the effort we are making in Italy, in order to make progress in the field of the industrial economy, results in an equivalent development in the commercial sector, because every sector has the obligation, the duty and the honour to contribute to the progress of this country’.

By the time the first guests and the authorities began to leave, darkness had already fallen, leaving only the staff in the store to celebrate with a congratulatory toast. The inauguration now a thing of the past, the new Rinascente had officially become a ‘true Roman’”.

How a department store came to life. Each new Rinascente, each new Upim iis like launching a ship Cronache Rinascente Upim”, anno XV, numero 26, 1961

26 — La Rinascente Roma piazza Fiume, 1965 ca., in “La Rinascente: cinquant'anni di vita italiana. Volume terzo”, 1968

Archivio Amneris Latis

“On Monday 18 September at 9 am, a sturdy and stocky middle-aged gentleman dressed in grey wearing a large pair of tortoise-shell glasses arrived at the same time as the first crowd that filled the corridors, the escalators and all the departments of the new store in Piazza Fiume with a jovial buzz. Many shop assistants recognised him; someone had even greeted him with a deep respect. Instead of stopping to browse the “September offers" at the special sales counters or to buy a toy for their grandchild, the unusual visitor at some point pulled out a large note pad from his jacket pocket and started taking notes.

Page after page of very dense notes became memos, recommendations, letters and circulars in a few hours, when the visitor was back in Milan. The man was Mr Giuseppe Boracco, the director of the Rinascente Technical Office whose watchful eye on the morning of 18 September searched for constructive critiques for the “blemishes" of the new store. For the past twenty-three years, Mr Boracco had been the father of all the new Upim locations and stores, and for some months the supermarkets of the SMA subsidiary; he had opened four Rinascente stores and played a part in revamping the others. Boracco had opened and redid 90 stores just for Upim alone.

[…] It is here in the Technical Office that every new Rinascente comes to life. [...] In a little more than nine months, the Rinascente stores in Genoa and Roma Fiume were prepared and got up and running, and are among the most modern and functional in the world.

“With a touch of emotion and, it must be said, a dash of pride Mr Boracco, told us that “Every Rinascente (and every Upim as well) is a bit like a ship. It is set up in the shipyard and prepared at the ports. The preliminary work that, starting with choosing the town for the new store, is split into the stages of deciding the exact area where the store will be built, the study of the market and the environment, the acquisition of the land, the first outline for the design and adapting this design to environmental requirement. Then comes the launch day. There is no sponsor smashing the bottle of sparkling spumante wine against the bow. At most, on the day when the masons finish covering the roof and fly the Italian flag atop, they had to a local trattoria for a risotto feast (in the north) or spaghetti all'amatriciana (in the south). The ship, that is the store, has been launched - all that is left is the reinforcement, or better put, the set-up of the store”.

27 — Rinascente Roma Piazza Fiume, in “Cronache laRinascente Upim” 1967, anno XX, numero 42

For months, the related problems had been examined and examined by architect Pagani, one of the leading European experts in the field of department store arrangement. His name is synonymous with the most brilliant achievements made by Rinascente in the post-war reconstruction and the subsequent development period including the stores at in Milan (Piazza Duomo), Catania, Genoa, and Rome (Piazza Fiume). At the stage, the possible solutions had been considered and the most difficult problems solved ahead of time thanks to the passionate work of the architect Ortelli, who was Pagani’s most enthusiastic collaborator and who brought the contribution of a specific and in-depth knowledge of the needs of the department store.

The similarity with the ship is not completely ridiculous. Every Rinascente is in fact a small independent unit. Mr Boracco takes a short rest after each inauguration. He stays in his study, examines the samples of countless items, even some things which are unthought of, such as small tiles for wall coverings, glass windows, and lamps. He also makes calculations of the wear of materials and is able to provide useful data to anyone requiring it. He had, for example, a piece of “parquet” on his desk: at that time, the heels of female shoes caused the irreparable ruin of wooden and rubber floors. “Fashion now costs us millions. It forces us to pave the floors with marble or other materials, as stiletto heels have made floors resemble the face of a smallpox-stricken person,” he concluded bitterly, agreeing that in the stores the flooring of the ground floor must be made of siliceous marble, while on the upper floors particular plastic materials or “carpet" are suitable. A stone's throw from Central Management’s new headquarters, the Politecnico di Milano often helps to find a solution, with its department dedicated to studies and experiences, to lend a hand to the efforts of the Technical Office. Other branches are now being studied. Where? It is a bit of an office secret. Mr Boracco's studio recalls, in some detail, one where top-secret designs of new models are developed in car factories.

The work of engineer Adolfo Rivarola, of the Rinascente Real Estate Office, who headed the work projects, and surveyors Mario Boffini and Castelli, are to be remembered (we apologise for any unintentional omissions).

Though 1961 was a tough year for the Technical Office, as well as for the new store in Rome, it will remain a memorable year nonetheless. As everyone knows, over the past few weeks the fifth and sixth floors of the Duomo store, where the offices had previously been located, were opened as sales floors. With the numerous changes the need to install a whole new system of escalators arose, an operation that had to be done at night. The façade has been broken, however, the six ladder trucks weighing 13,000lbs. each, and have been put in place and work very well. All through the night (a ladder every night) so as not to hinder sales during the day. After the preparation for Rome, they were the last “all-nighters” for the men of the technical office. And because of this we believe that this mention in “Cronache" is a belated way of saying “thank you”’.